Haudenosaunee Historical Context in the War of 1812 and the Defining Events of the Battle of Queenston Heights

Rick Hill

Six Nations Legacy Consortium

June 2011

Background

The Haudenosaunee (Six Nations) were pulled in two different directions because of conflicting treaty obligations. There were two Covenant Chains, one with the British Crown and one with the American Congress. The Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida, Mohawk and Tuscarora people were not only scattered physically across their former territory, they could not come to one mind on what to do. There was no single Haudenosaunee response to the war. Even within each nation there were divided loyalties.

The Peace Chiefs wanted to remain neutral, but lingering animosities from the American Revolution set various communities at odds with one another. The Chiefs at Buffalo Creek in western New York did not see eye to eye with the Chiefs at Grand River in Ontario. Pleas for neutrality fell on the deaf ears of the warriors. Once the British invaded Grand Island, the Senecas felt compelled to declare war on England. Once General Brock was killed, the Grand River warriors thirsted for revenge that led to the total destruction of the Tuscarora community. What remained of the legendary Great Peace seemed to disappear.

However, the horrors of war stopped even the toughest warriors in their tracks. The blood shed between brothers at Chippewa, Queenston Heights, and Beaver Dams forced the warriors to question their motives. What were they really fighting for? Most agreed to withdraw from the fighting and return to protect their families.

After the war, calls for reconciliation led to a historic peace council in which the former combatants, and their British and American allies, condoled each other for their losses, buried the weapons of war and agreed to become one people again. Despite the divided loyalties during the war, the Haudenosaunee merged as one people once again and have since been at peace with each other.

The American newspaper, Nile’s Weekly Register, published a story on the use of First Nations as allies, condemning the British because,

The savages were brought into the war, upon the ordinary footing of allies, without regard to the inhuman character of their warfare. . . While the British troops behold, without compunction, the tomahawk and the scalping knife, brandished against prisoners, old men and children, and even against pregnant women, and while they exultingly accept the bloody scalps of the slaughtered Americans, the Indian [exploits in battle, are recounted and applauded by the British general orders].

(Niles’ weekly register, Volume 8, By Hezekiah Niles, William Ogden Niles)

August 18, 1812 – U.S. Brigadier-General and Commander of the Northwest Army William Hull issued a proclamation to the people of Canada:

If the barbarous and savage policy of Great Britain be pursued, and the savages are let loose to murder our citizens, and butcher our women and children, this war will be a war of extermination. The first stroke of the tomahawk – the first attempt with the scalping knife, will be the signal of one indiscriminate scene of desolation. No white man found fighting by the side of any Indian will be taken prisoner; instant destruction will be his lot.

(Brigadier-General William Hull, “A Proclamation,” reprinted in the Kingston Gazette, 18 August 1812, in Arthur Bowler, The War of 1812, (Toronto: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1973), p. 52-3.)

British General Isaac Brock came to the defence of his allies and published a response that stated that the Haudenosaunee only retaliated for any brutality done to them.

Leading up to Queenston Heights

In June 1812, before the outbreak of the War, Seneca warriors and leaders, along with representatives of the Onondaga and Cayuga, traveled to meet with the Haudenosaunee at Grand River. They argued for neutrality but could not come to one mind on the matter. Too many chiefs and warriors at Grand River, perhaps still stinging from their losses during the American Revolution, wanted to defend the interests of the King, despite that this might lead to confrontations with the Confederacy nations.

The Grand River Chiefs made a statement to the Indian Department officials that the friendship between the Haudenosaunee had ended. Seneca delegate Hure-hau-stock (Capt. Strong) tried to deliver a wampum belt, but the Grand River delegates would not receive it.

After the war broke out, a second delegation of Onondaga and Senecas met with the “pro-British” faction from Grand River at Queenston. This time General Brock had more influence on the council and Norton stacked the deck of delegates in the Crown’s favor. Only a few delegates were allowed to cross the Niagara River, and they were only given a few minutes to present their case.

Seneca speaker Arosa (Silver Heels), holding a wampum belt, spoke of the miseries and destruction brought on by war. He reminded the Grand River delegates that it would be tragic if old friends found themselves fighting each other.

Brothers, the people of the great King are our old friends, and the Americans are our neighbours. . . We have determined not to interfere, for how could we spill the blood of the English or of our Brethren? We entreat you therefore to imitate our determination. . .

Listen to the words of our Mothers, they are particularly addressed to the War Chiefs, they entreat them to be united with the village chiefs, and to have a tender regard for the happiness of their women and children and not to allow their minds to be too much elated or misled by sentiments of vanity or pride.

The Grand River chiefs would not agree to neutrality. In response Arosa pleaded:

Let the Warrior’s rage only be felt in combat, by his armed opponents; – Let the unoffending Cultivator of the Ground, and his helpless family, never be alarmed by your onset, nor injured by your depredation.

(The Journal of Major John Norton 1816, Carl F. Klinck and James J. Talman, editors, The Champlain Society, 1970, pp. 289-292)

The United States Congress declared war on Britain on June 18, 1812. It was not until August 24, 1813 that the Six Nations Council at Buffalo Creek would declare war on Britain. The principal chiefs who led the Seneca warriors were Farmers-Brother, Red Jacket, Little Billy, Pollard, Black-Snake, John, Silver-Heels, Captain Half-Town, Major Henry O’Bail, and Captain Cold.

When the July 12, 1812 invasion of Canada began in Detroit, U.S. Brigadier General William Hull, Governor of the Territory of Michigan, and Commander of the Northwestern Army of the United States, sent notice to Grand River that their settlements and families would not be disturbed if their warriors would remain at home.

General Brock became enraged by the lack of support from Grand River and threatened to remove them to the west. Brock sent Joseph Willcocks to Grand River to try to win back their support. Willcoks had been a member of the Legislative Assembly of Upper Canada representing Haldimand County, but had also become a political foe of Brock. He resisted Brocks attempts to prepare for war, yet found himself fighting alongside the Six Nations warriors who were part of General Roger Hale Sheaffe’s ultimately successful retaking of the Redan Battery.

Norton refused to abide by the Grand River council’s policy of neutrality and went into battle with 60 Grand River warriors, but half of them returned before any action.

Norton had met Brock on September 6, 1812 at Fort George and he sent word to the Grand River for the chiefs and warriors to assemble at the fort with all possible speed because Brock thought the American attack was imminent. Norton stuck his hatchet in a war pole and the warriors, dressed and painted for battle formed around, each man giving the chief a piece of wood painted red as a symbol of his commitment to the coming battle. Songs were sung, war drums beaten and the war dance followed. One eyewitness described such dances:

I have seen Mr. Norton go through it Several times in his Country when properly performed Three or four stand near & sing a particular tune [celebrating the dancer’s exploits] which is accompanied by the drums; they then get up in pairs & represent a battle; they first advance leaping from side to side with astonishing agility . . . I observed when Mr. Norton danced that his whole appearance was instantly changed – instead of being mild and humane, his countenance assumed a most savage & terrific look . . .

Sir George Prevost ordered that the officials in the Indian Department (namely Claus) not to interfere with Norton. By July 1812 Norton had a force of 200 Haudenosaunee warriors assembled at Niagara. Brock was very disappointed in the lack of warriors.

At the same time, Maj. Gen. Jacob Brown with a force of 500 Buffalo Creek Haudenosaunee, including Seneca, Onondaga, Tuscarora and Oneida warriors under the command of General Porter and Seneca war chief Red Jacket crossed over to Fort Erie and quickly took the fort. Then they headed to Chippewa.

The Events of August 13, 1812

John Norton, of Scottish and Cherokee ancestry, was the adopted nephew of Joseph Brant, and by some accounts was made a Pine Tree Chief at Grand River. Prior to the war Norton was pursuing his uncles’ campaign for justice from the Crown for the land rights on behalf of the Council at Grand River. He was also at odds with the head of the Indian Department William Claus and there was a constant battle within the pro- and anti-Norton factions at Grand River.

Major-General Francis de Rottenburg who served as the military administrator of Upper Canada remarked: “All my endeavours to reconcile . . . [Claus] and Norton are in vain, the latter is certainly a great intriguer, but is a fighting man – and may do a great deal of mischief if not supported.

Norton and the 200 warriors who fought at Queenston have been credited by both eye witnesses and subsequent historians as providing essential support and diversion to hold off the American advance until British reinforcements arrived from Fort Erie.

One eye witness gave this account:

The Indians were first in advance. As soon as they perceived the enemy they uttered their terrific warwhoop, and rushing rapidly upon them commenced a most destructive fire. Our troops instantly sprung forward from all quarters, joining in the shout. The Americans gave a volley, then tumultuously fled by hundreds down the mountain [towards the river).

Another account:

[Norton’s] brilliant tactical decision to take a “circuit” meant an ascent of the escarpment at a considerable distance along the road west of Queenston, and a climb easier than that attempted by Major-General Isaac Brock on the cliff close to the Niagara River. The woods on the right flank of the American force moving westward along the heights were precisely what Norton and his Indians needed for cover as they pinned down the enemy’s advance until Major-General Roger Hale Sheaffe and his troops came up to sweep the Americans off the heights. Reinforcements from Chippawa also arrived.

Sheaffe mentioned in his dispatches “the judicious position which Norton and the Indians with him had taken.” One week after the battle, on 20 October, Sheaffe honoured Norton by appointing him “to the Rank of Captain of the Confederate Indians” – the same rank that Joseph Brant had held during the American revolution. Sir George Prevost*, governor-in-chief of British North America, congratulated Norton upon his courage and perseverance, with advice “to keep up and increase the numbers of a description of Force so truly formidable to their Enemies and so capable of sustaining the good cause in which we are engaged.”

(Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online at Libraries and Archives Canada)

Sheaffe was so impressed by the Norton countermove, he awarded him rank as Captain of the Confederated Indians.

The oral history of the Haudenosaunee states that Brock was warned by his Grand River allies not to attempt the assault as he planned. His death deeply affected the Grand River warriors who retaliated with great force in subsequent engagements.

Those who fought at Queenston Heights

Lt. James Fitzgibbon of the 49th Regiment of Foot, provided this description of general Haudenosaunee fighting tactics that would have been employed at Queenston Heights. :

The Indians, when retreating and coming to a ravine, do not at once cross the ravine and defend from the brow of the side or hill looking over the ravine to the pursuing enemy; they suddently throw themselves down immediately behind the bank they first come to, and thence fire on their pursuers, who must then be entirely exposed, while the Indian exposes his head only, and when pressed and compelled to abandon his position, he fires and retires, covered by the smoke and the bank, so that his pursuers cannot tell the course of his retreat, whether to the right or the left, or directly to the rear, which last the Indian may now do with comparative safety, being for a short time hid by the bank from the view of his pursuers, until he, the pursuer, arrives at the brow of the bank, by which time the Indian has, most probably, taken post in a new position, where he can only be discovered by his next fire.

Those involved in the conflict:

According to Ron Dale of Parks Canada there were only 100 Delaware and Six Nations warriors at the Battle of Queenston Heights on August 13, 1812. There may have been a few warriors from the Mississauga, Tyendinaga Mohawks of the By of Quinte, and Anishinaabe, however, the records are not definitive.

For Six Nations, the following men were listed as war captains or leaders:

Ah’you’wa’eghs (John Brant, 1794-1832), son of Joseph Brant

Teyoninhokarawen (John Norton)

Toowaghwenkaraghkwen (Thomas Davis)

Kenwendeshon (Aaron Hill)

Karaghkohtye (David Davids)

Killed in action that day:

Cayuga chiefs named Ayanete and Kayentaterhon

Onondaga warrior named Ta Kanentye

Oneida warriors, named Kayarawagor and Sakangongu’quate.

The Americans suffered well over 300 killed and wounded and 958 taken prisoners.

Brock Condolence

On November 6, 1812, at a general Council of Condolence held at the Council House at Fort George with the Six Nations, Hurons, Chippewas, Potawatomies, and others, Kodeaneyonte, Little Cayuga, chief speaker, condoled the British for the death of General Brock at Queenston. Holding wampum strings he stated:

Brother, — We, therefore, now seeing you darkened with grief, your eyes dim with tears and your throat stopped with the force of your affliction, with these strings of wampum we wipe away your tears, that you may view clearly the surrounding objects. We clear the passage in your throats that you may have free utterance for your thoughts, and we wipe clear from blood the place of your abode, that you may sit there in comfort without having renewed the remembrance of your loss by the remaining stains of blood.

He then gave a large white wampum belt with these words:

Brother, — That the remains of your late beloved friend and commander. General Brock, shall receive no injury we cover it with this belt of wampum, which we do from the grateful sensations which his friendship towards us continually inspired us with, as also in conformity to the customs of our ancestors, and we therefore now express with the unanimous voice of the chiefs and warriors of our respective bands the great respect in which we hold his memory, and the sorrow and deep regret with which his loss has tilled our hearts, although he has taken his departure for a better abode, where his many virtues will be rewarded by the great dispenser of good, who has led us on the road to victory.

Kodeaneyonte concluded:

We also assure him [Brock’s successor] of our readiness to support him to the last, and therefore take the liberty to exhort him to speak strong to all his people to co-operate with vigor, and trusting in the powerful arm of God not to doubt of victory. Although our numbers are small, yet counting Him on our side who ever decides on the day of battle, we look for victory whenever we shall come in contact with the enemy.

(Canadian Archives, C. 256, p. 194.)

Those who contributed to the Monument

Based upon one accounting of the £207 10s contributions to the rededication of the Brock Monument in 1912, was made on behalf of the following:

- The Chippewas of the Upper Reserve, on the River St. Clair.

- The Chippewas of the Lower Reserve and Walpole Island, on the River St. Clair.

- The Hurons and Wyandotts of Amhersthurg.

- The Chippewas of the River Thames.

- The Munseee of the River Thames.

- The Oneidas of the River Thames.

- The Six Nation Indians of the Grand River

- The Mississauga of the River Credit

- The Chippewas of the Saugeen River, Lake Huron.

- The Chippewas of the Township of Rama.

- The Chippewas Of Snake Island. Lake Simcoe

- The Mississauga of Alnwick, Rice Lake.

Aftermath

At the Battle of Chippewa, Sagoyewatha (Red Jacket), who was in his 60s, leads Seneca warriors against 200 Grand River warriors led by John Norton. Norton and his men came upon 87 of their kinsmen who were killed in the American-Seneca assault. The Senecas later counted 25 of their own dead and many others wounded. Oneida Chief Cornelius Doxtator was also killed that day.

In 1813 Seneca leader Sagoyewatha (Red Jacket) dispatched two young chiefs to the British encampment at Burlington to meet with Grand River leaders and others allied with them to make a proposal for a mutual withdrawal. The Buffalo Creek chiefs stayed three days discussing the subject with their kinsfolk with whom they dared to communicate. Returning they reported that the idea was acceptable.

Both sides took a deep breath and weighed their options. Less than two weeks after the battle, the opposing warriors met in council, agreeing to end the fratricide. Both sides decided to withdraw from combat and went back to their homes.

The Senecas now agreed to withdraw to their own villages, and return to the battle only when the British Indian allies should again take to the war path. Thus over six hundred Haudenosaunee in New York continued in readiness, resting in their villages, but taking no concerted part in the subsequent campaign.

Reconciliation

At the end of August, 1815, a council of reconciliation took place at Niagara. On the “American side” of the fire were Senecas, Onondagas and Cayugas from Buffalo Creek, Tonawanda and Allegheny. On the “Canadian side” were people from the Grand River Territory.

The council began with “the usual ceremonies of Condolence” by the Crown’s representative, but the Haudenosaunee immediately took over the work of peacemaking. By the end of the process, the Haudenosaunee had “mixed together” and become “one people” once again. While the council was lengthy and officially at the “King’s Council Fire,” it was a good example of internal Haudenosaunee reconciliation processes. While the British opened the council, the first day consisted of the propositions of the Grand River chiefs, and the “American side” chiefs replied the next day. Echo, an Onondaga Chief, stated:

“To make our Friendship lasting, we put the Tomahawk the depth of a Pine Tree under ground; and that it may not be removed we place over it a Tree that the roots may so cover it that it cannot be found again. This ceremony was performed by our Father at Burlington last Spring in presence of the Western Nations and I will now repeat to you the speech which our Father delivered to us when he informed us of the Pacification with the Americans, and our Answer (here the proceeding of the Council at Burlington last Spring on the 24th, 26th and 27th April last was repeated). We condole with you from the bottom of our hearts for the loss of your friends, and wipe the tears from your eyes, we open your throats so no obstruction shall remain, that you may speak your mind freely and with the same friendship which formerly existed between us, as we now in the name of the Nations already mentioned address you as friends. If you will stand up we will take you by the hands. Should an idle young Man make use of any improper Language we request that you will not take any notice of it.”

Seneca war leader Red Jacket, representing the Haudenosaunee from Buffalo Creek, responded:

We are not of the same Nations only, but of the same Families also. We therefore ought to be united and become on Body…. We seriously recommend that your people will now attend to your usual occupations of hunting and agriculture and that you pay due attention to your Women, who by our ancient customs have a voice in bringing up our Young people to the practice of truth and industry.

(DCB vol. VI: 759-760; MPHSC vol. XVI: 263-265; PSWJ vol. XII: 628).

The Deputy Superintendent General, Col. William Claus responded:

. . . The Road has been open’d and made smooth for you all. When the King of England made peace with the Americans he was particular in stipulating that no difficulties should be thrown in the road to interrupt a free intercourse between his Indian Children.

On October 13, 1824 several Six Nations chiefs returned to Queenston Heights to be part of the procession that carried Brock’s remains to their new resting place at the first monument built to honor him.

“Mr. Brant, as a chief of his race, and other Indian Princes, arrayed in their native garb, made part of the procession, and appeared to take a deep interest in the scene.” (“The anniversary of the Battle of Queenston,” The Advocate, Oct 14, 1824)

The William Claus Wampum Belt

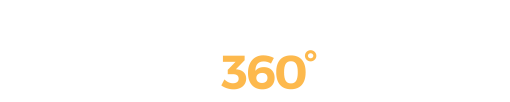

September 14, 1871 – The above photograph was taken by Foster photography of Clinton, Ontario for anthropologist Horatio Hale. It shows some Grand River Chiefs holding several wampum belts that were still in their possession at that time. Chief John Smoke Johnson, Pauline Johnson’s grandfather, is standing, holding a wampum belt that was given by British Indian Department Agent, Col. William Claus, at the conclusion of the War of 1812.

The same belt is seen in the center of this photograph, taken by Hale in 1871. The photo is from the Pitt Rivers Museum, England.

Deputy Superintendent General, Col. William Claus (1765-1826), was the grandson of Sir William Johnson, son of Colonel Daniel Claus, nephew of Sir John Johnson, Superintendent General of Indian Affairs. The Imperial Indian Department remained under Johnson family control from 1755 to 1830

In 1800, Claus was appointed Deputy Superintendent General Indian Affairs for Upper Canada. He had been opposed to Joseph Brant assertion that Six Nations had the right to sell their land. He developed animosity for Brant’s adopted nephew, John Norton, who had influence among the people at Six Nations.

After the war the Crown moved to solidify the loyalty of the Haudenosaunee. This wampum belt was created to represent their ongoing relationship. The pattern may have been derived from an ancient design called the meander or Greek Key. It often was used to represent the bonds of love and friendship. Notice that the belt is finished differently than it is now, appearing that some beads have been removed from the ends.

On April 15, 1815 Claus held a great council at Burlington with delegates from the Hurons, Six Nations, Shawanoes, Delawares, Kickapoos, Chippewas, Otawaws, Saukies, Misquakies, Creeks, Munseys, Moravians and Nanticokes. He began by wiping the tears from those who have lost comrades during the war:

The ceremony of condolence for the loss of our near and dearest relations and friends, now must be performed, which I now do very sincerely. The Great Giver of Life has been pleased to remove from this world many of our Friends and Relations. Your eyes are so full of tears that you cannot see clearly. Your Ears and Throat are stopped up, your Hearts have been in trouble and grief, your Limbs are still covered with mud, your feet are full of thorns, and your seats are still covered with blood. I now therefore dispel the cloud that hangs over you, and wipe the tears from your Eyes that the brightness of the sky may again appear to you. I open your ears that you may hear distinctly, and I free your throats from all obstructions, that you may speak freely and with care. Your Hearts I replace, and remove all grief and trouble from them, and I hope you will listen to nothing but what is good. I wash the mud from your legs, extract the thorns from your feet, and I cleanse from your Seats the blood which now covers them, that you may again sit on them with comfort.

I now gather together the bones of those dear Friends and relations whom it has pleased the Great Spirit to remove from this world. I place them all in one Grave, and to prevent all briars and rubbish from collecting thereon, I cover it with this Belt.

Of the Wampum Belt illustrated above, Claus noted:

. . . to inform you that Peace has been concluded, and that all hostilities are to cease between your Great Father’s children and the Americans, and it is his earnest wish for the sake of your Women and Children that you join sincerely in this Peace. It is therefore my duty to inform all the Nations here assembled, that the Hatchet which you so readily took up to assist your Great Father, should now be laid down and buried, that it may not be seen. This is the earnest wish of your Father the King, and I am confident you will comply with cheerfulness. You have fought and bled in the cause which you espoused and your Father is sensible of the value of your friendship and services. This Belt which I now hand to you I ask in compliance with your Customs be sent by you with these my words in his behalf to all the Nations in friendship with your Great Father the King of England. . .

I am further instructed to inform you that in making Peace with the Government of the United States of America, your interests were not neglected, nor would Peace have been made with them had they not consented to include you in the Treaty, which they at first refused to listen to. I will now repeat to you one of the Articles of the Treaty of Peace which secures to you the Peaceable Possession of all the Country which you possessed before the late War, and the Road is now open for you to pass and repass without interruption.

I now look towards the Sachems and principal Chiefs, who after the Hatchet is laid down by the War Chiefs and Warriors, will again take their Seats in front of the Warriors, and resume their duties whilst the others return to their hunting and other occupations. Your Great Father’s Council Fire will again be kindled at the usual posts, the smoke from which will be seen by all the Nations around you.

[NAC RG8 C Series Vol. 258 pt. 1 pp. 60-70a]

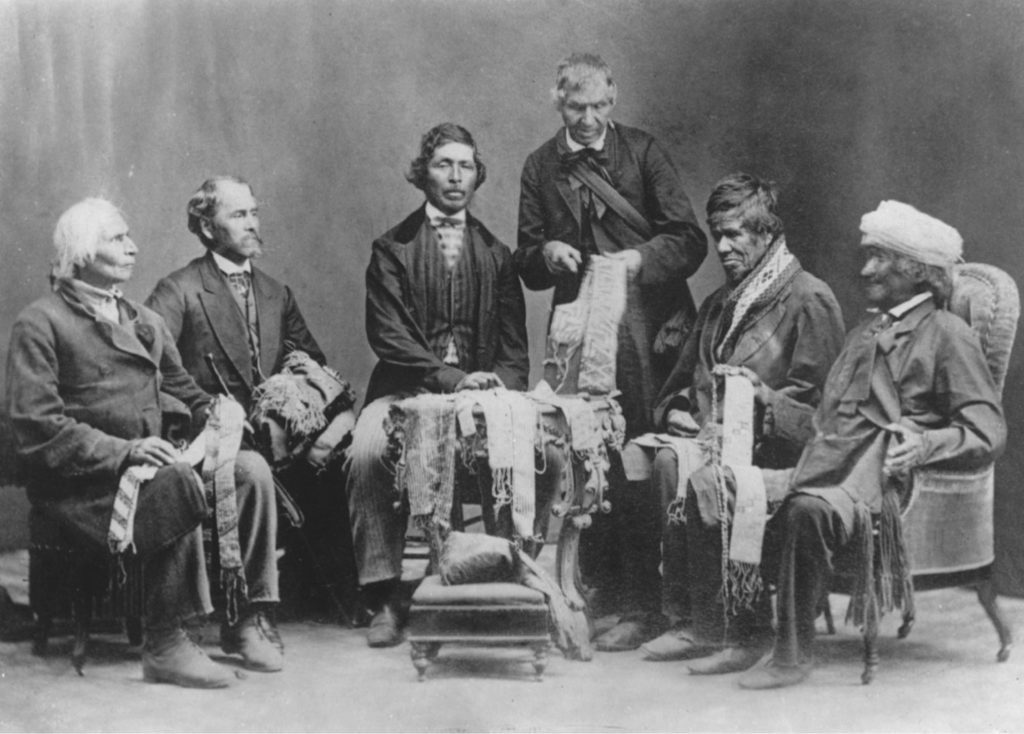

The belt was obtained by Pauline Johnson after the death of her father, who had continued to hold the belts his father had. Her sister, Evelyn, loaned four wampums to the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, with the agreement that they would not be published or displayed until after her death, at which time the loan would become a gift to the museum. Evelyn was fearful of what might happen if the traditional Longhouse people found out that she illegally removed the belts which were supposed to revert to John Buck the Confederacy Wampum Keeper at Grand River. Those wampum belts have since been repatriated to the Grand Council of Chiefs at the Grand River Territory in 1999.

Other belts were sold by the family of the wampum Keeper, John Buck, who is also seen in the top photo (to the left of Chief Johnson). Pauline used some belts as part of her costuming for her dramatic readings of property and lectures .

She sold this belt to George Heye for $500 to finance one of her trips to Europe in 1906, with the intention of buying it back when she returned. (Betty Keller, “On Tour With Pauline Johnson,” The Beaver, Hudson’s Bay Company, December 1986-January 1987)

However the trip was not a financial success and she was not able to repurchase the belt and Heye kept it for his collection. The letters from Johnson to Heye on the wampum are in the archives of NMAI. There is one photo seen below that shows Pauline Johnson with the Claus belt.

In 1908 George Heye agreed to loan objects to the University of Pennsylvania for their exhibitions. It is assumed that this belt was at the museum from at least 1910. Frank Speck, an ethnographer who taught at the University of Pennsylvania recognized that some of the wampum on exhibition were those reported to have been stolen from Grand River. Heye then withdrew some of his collection from the University Museum in 1912, but the wampum belts remained on view.

When the Haudenosaunee requested the return of their wampum belts from NMAI, this particular belt was missing and removed from the inventory requested.

Lucy Williams, Keeper of the American Section Collections at the University Museum, explained to the curators at NMAI that in 1996 Elisabeth Tooker, in preparing a report for the museum, discovered a faded Heye Collection tag on the missing NMAI wampum belt. Upon closer examination the object number “8386″ was revealed. The University Museum contacted NMAI and returned the belt. NMAI Collections Staff notified the Haudenosaunee Standing Committee of the discovery.